Las Vegas NWR--Gallinas Canyon

Las Vegas NWR--Gallinas Canyon

Las Vegas, New Mexico 87701

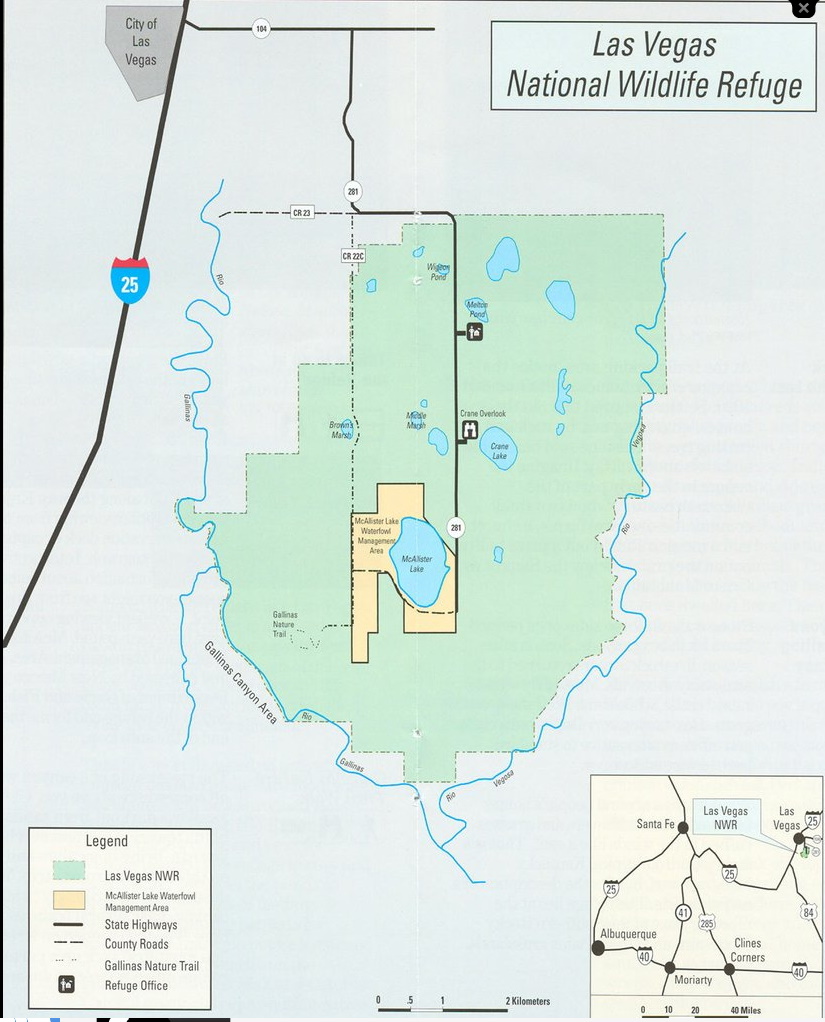

Las Vegas National Wildlife Refuge Official WebsiteLas Vegas National Wildlife Refuge map

Tips for Birding

Gallinas Canyon is one of the top ten hotspots in the county, ranked by species, partly because it includes at least 3 distinct habitats, all of which may be experienced by hiking the mile-long, lollipop-shaped Gallinas Nature Trail. In fact, the trail does not reach or overlook the Gallinas River canyon, but after traversing short-grass prairie, favored by Western Meadowlark and Scaled Quail, east from the trailhead off County Road 22C for almost half a mile, meets the beginning of a smaller, northeast-to-southwest oriented, unnamed side canyon. Look for Rock Wren here.

After following the rim of the widening side canyon less than a hundred yards, you pass through a barbed-wire fence gap, then veer away from the side canyon, setting your eyes on the ruins of a rock building across the prairie to the south. This is a deviation from the route appearing on the Refuge’s website, which includes a portion very difficult (and even somewhat hazardous) to follow on the ground. That route continues skirting the side canyon’s rocky south rim, then forms a semi-circle west of the ruined structure. The two routes join south of the ruins, but the rim path is easy to lose whereas the more direct prairie route is obvious. You won’t miss any birds by taking the direct route.

Shortly after passing the ruins, you begin to descend west into the side canyon, with the habitat becoming more of a juniper woodland. At this point, you’ve lost your cell phone connection. In spring and summer, Broad-tailed or Black-chinned Hummingbirds may investigate you on your way down, particularly if you’re wearing bright colors. In just 250 to 300 yards, you reach the canyon bottom, where there is a seep. Be cautious of poison ivy here! It grows around the flat rocks that invite you to sit for a rest after your descent, though you’ll probably be eager to keep moving during summer to escape the many mosquitoes.

Stepping over the narrow flow out of the seep, you encounter the loop portion of the “lollipop”. Taking this loop clockwise, heading southwest on the more level ground, the trail continues just above the willows of the riparian habitat at the bottom of the canyon, with juniper and ponderosa pine upslope to your right. Riparian species such as Wilson’s Warbler and Yellow-breasted Chat may be seen seasonally along this stretch of trail. In less than 200 yards, you the trail turns sharply north, but listen for Canyon Wrens here before you ascend into a forest comprised progressively of more ponderosa. American Robin, and in fall Townsend’s Solitaire, may be encountered in this habitat. The loop is only about a third of a mile long, and after passing above another seasonally active seep near the trail’s highest point, you quickly descend, making a full circle.

Despite the Nature Trail being slightly over a mile long, a large number of lists for this hotspot show incredible multiples of that length as effort, 5 miles or more. These records cover an area much beyond the Nature Trail; indeed, the hotspot map pin is located more toward the mouth of the side canyon than is reached by the trail. Possibly those more-extensive-effort lists reflect observations made in the main Gallinas River canyon, though this is physically quite challenging to reach from the Refuge side of the river. In order to preserve natural landscape beauty, The US Fish and Wildlife Service has installed only a few “area closed” signs here and asks that visitors remain on the Nature Trail. It could be that the majority of lists at this hotspot were recorded by researchers with access not afforded to the general public. Regardless of the reason, visitors should not expect to observe from the trail anywhere near the variety and number of birds indicated by eBird species-frequency data related to this hotspot.

A final tip: From April through September, be alert to the presence of rattlesnakes.

Birds of Interest

Broad-tailed Hummingbird, Northern Harrier, and Ferruginous Hawk

About this Location

The Gallinas Nature Trail (1.75 miles) is a self-guided nature trail that meanders through fields of native grasses and wildflowers, past historic ruins and descends approximately 250 feet into one of the many box canyons that surround the refuge. As you descend into the canyon, you will find an oasis in this arid zone, a small seep, surrounded by vegetation, which provides habitats for an assortment of small fish, amphibians, crustaceans, and aquatic insects. Continuing on the loop trail, on the western side of the canyon, enjoy being surrounded by the sweet smell of piñon, juniper, and ponderosa. Along this walk, listen for the call of a canyon wren and keep a look out for wild turkey ahead or American kestrel up above.

The trail is open from sunup to sundown 7 days a week and is self-guided.

About Las Vegas National Wildlife Refuge

See all hotspots at Las Vegas National Wildlife Refuge

Spanish for "the meadows," Las Vegas National Wildlife Refuge’s history dates as far back as 8,000 BC when old-world Indians inhabited the high plains area.

Pueblo Indians also spent time living in this region, until the 1100s when drought and Apaches forced them out. In the mid-1500s, Spanish conquistadors and missionaries explored and settled the region, and the influence of Spanish culture is still felt today. Westward expansion continued in the late 1800s, and by the turn of the century, the Santa Fe Trail and the railroad made Las Vegas, New Mexico, the place to be.

In 1965, the Las Vegas National Wildlife Refuge was established by the authority of the Migratory Bird Conservation Action for the benefit of migratory birds. The 8,672-acre refuge represents one of the few sizeable wetland areas remaining in New Mexico. It is open to the public for wildlife-dependent recreation, including wildlife watching, hiking, hunting, educational and interpretive programs, and special events.

Here, the gently rolling prairies of the east abruptly meet the rugged terrain of the mountains, gravel-capped mesas and buttes, and deep, narrow river canyons. The high plains refuge is surrounded on three sides by steep, timbered canyons but within the habitat, there is short and tall-grass prairie, timbered sandstone canyons, piñon-juniper woodlands, wetlands, ponds, lakes, and riparian areas.

Above the timbered canyons, the refuge encircles more than 40 small ponds that provide tubers, seeds, and browse for waterfowl. In addition to the ponds, a number of springs discharge to the surface and support a variety of species, including several native fish like the Rio Grande chub, longnose dace, white sucker, and fathead minnow. These ponds are critical to birds migrating along the Central Flyway as they depend on the refuge as a place to rest and refuel during their long journey.

Nesting on the refuge are nearly one-third of the documented bird species found on the refuge, including long-billed curlews, avocet, Canada geese, mallards, northern pintails, blue-winged and cinnamon teal, gadwall, and ruddy ducks.

The sandhill cranes arrive in the fall as they migrate to their winter home. Bald eagles, northern harriers, and American kestrels are frequently sighted soaring above the refuge scanning the grasslands for prey or attracted to the hundreds of ducks and geese on the refuge’s open waters. Migrating shorebirds like long-billed dowitchers and sandpipers, probe the mudflats in early fall and spring. In the woodlands, wild turkeys wander in search of a meal, and on the prairies. Rocky Mountain elk blend into the grasses, home to badgers and ground squirrels.

Features

Restrooms on site

Wheelchair accessible trail

Entrance fee

Content from Las Vegas National Wildlife Refuge Official Website and John Montgomery

Last updated September 24, 2023