Maximizing the Value of Your eBird Checklists from the Mountains

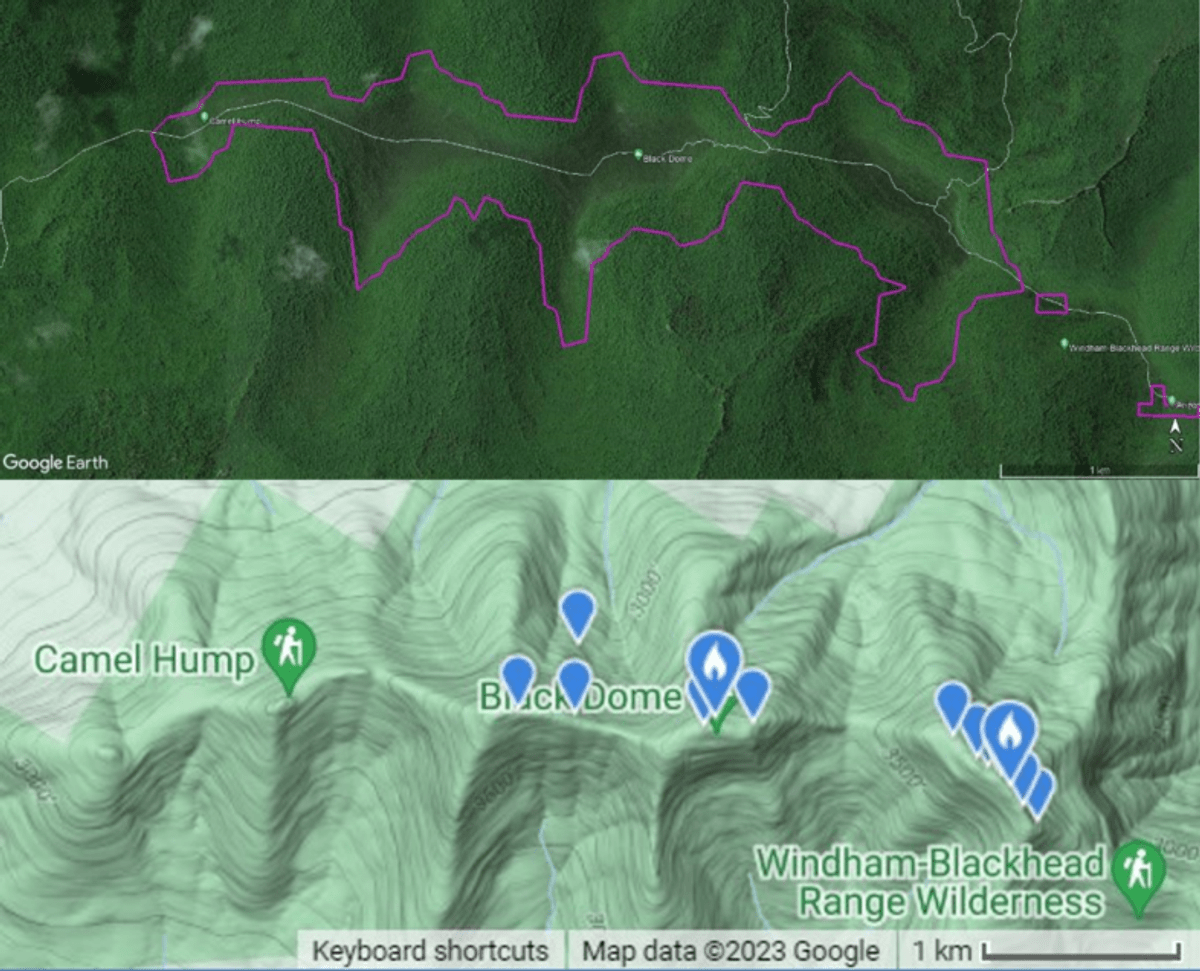

Both panels show the Black Dome ridgeline (and surrounding mountains) in the Catskills of New York. The top panel shows the estimated extent of the high-elevation spruce-fir forest, outlined in purple. The white lines are hiking trails. High-elevation species like Bicknell’s Thrush are likely found throughout the area outlined in purple. This imagery is from Google Earth. The bottle panel shows the same area, with an image created by eBird on 8/3/2023. The blue markers in the bottom panel show where Bicknell’s Thrush have been previously reported to eBird. Incredibly, there has only been a single checklist reporting Bicknell’s Thrush within this area to eBird within the last decade.

Both panels show the Black Dome ridgeline (and surrounding mountains) in the Catskills of New York. The top panel shows the estimated extent of the high-elevation spruce-fir forest, outlined in purple. The white lines are hiking trails. High-elevation species like Bicknell’s Thrush are likely found throughout the area outlined in purple. This imagery is from Google Earth. The bottle panel shows the same area, with an image created by eBird on 8/3/2023. The blue markers in the bottom panel show where Bicknell’s Thrush have been previously reported to eBird. Incredibly, there has only been a single checklist reporting Bicknell’s Thrush within this area to eBird within the last decade.

By Jason Hill

Vermont Center for Ecostudies

As a former eBird reviewer, I’ve seen all kinds of checklists (ranging from excellent to not) and even contributed a few less-than-stellar checklists of my own (e.g., birding from my bike and an airplane window, not at the same time of course, don’t be silly). Let’s get one thing straight; the quality of a checklist doesn’t necessarily have anything to do with the number of species or individual birds reported. A 10-minute checklist where you genuinely didn’t hear or see any birds (which has happened to me plenty of times in the mountains) is valuable.

In my experience, most birders who submit checklists to eBird.org (an online community science data repository for birding observations) have two objectives. First and foremost, they find it fun. People enjoy observing birds and appreciate the convenience of having eBird keep track of where they’ve gone and what species they detected. Second, many of those folks also hope their data can contribute to avian conservation and to our greater understanding of bird populations.

With that in mind, let’s cover some tips to increase the scientific value of your eBird checklists, especially from the mountains—the place where I do most of my birding. Having said that, all of the general eBird rules and best practices (e.g., reporting all species accurately and not recording dead or captive birds) also apply to your montane checklists.

Be still. Whenever possible, avoid turning a long hike (e.g., from the parking lot to the summit and back) into a single traveling checklist in the mountains. Montane bird species have strong elevational preferences, and elevation can be a strong predictor of abundance and distribution. So, strive to avoid checklists that include bird observations from large spans of elevation (>100 feet). For those of us who build models from eBird data, there’s no way to extract the elevation of every bird observed on a traveling checklist. Depending on the research question, scientists using eBird data may simply discard all traveling checklists over some specified length (e.g., 0.1 km). A better alternative for montane birding is to only conduct stationary counts, where you’re birding from a fixed location (and elevation). If you’re hiking a mountain, just stop every so often and conduct a stationary count instead of reporting all your birds from the hike on a single traveling checklist.

Put some new dots on the map. When we build distribution models from avian data (for example, to understand climate change impacts) we often impose a grid over the study area. We then determine the occupancy of each cell on the grid by overlapping eBird data from each species one at a time. If you’re the 30th person to report a particular species on a grid block in June of 2023, for example, then your data are largely redundant with others’ data. So, how do you increase the chances that your data actually contribute to a model and our understanding of bird populations? Easy–go birding where other folks do not. Unfortunately, eBird doesn’t have mapping tools to help find ‘under-birded’ locations. Your best bet may be to use the eBird mapping tool to see everywhere a species has been reported previously. For example, here are all of the Bicknell’s Thrush (Catharus bicknelli) observations in the Catskills so far in 2023—a meager two dozen checklists–yikes. I like to play with the Year filter settings to identify where a species hasn’t been seen in more than a decade.

Strive to add breeding bird codes to your checklists. There are so few birders in the mountains, compared to lower elevation areas, and even fewer folks adding breeding code data to their checklists. For example, if you accidentally flush a Dark-eyed Junco (Junco hyemalis) from its trailside nest while hiking atop Killington, stop to enter those data as an incidental checklist with the right breeding code (ON in this case for occupied nest).

Mountains are warming at a faster rate than almost any other non-polar area on the planet, and montane birds are expected to respond to climate change by moving upslope (when possible) and towards the poles. Documenting how quickly montane birds are able to respond to climate change is vital to identifying conservation strategies for these species. So, get out there and bird the mountains, and think about adopting a Mountain Birdwatch route.